How Sensory Learning Assists Math Skills

Everything we learn comes first through our senses. Babies are able to discriminate the sound of their parent’s voice, the shape of their family’s faces, the smell of milk, and the touch of skin. This is the beginning of a child’s learning about the world.

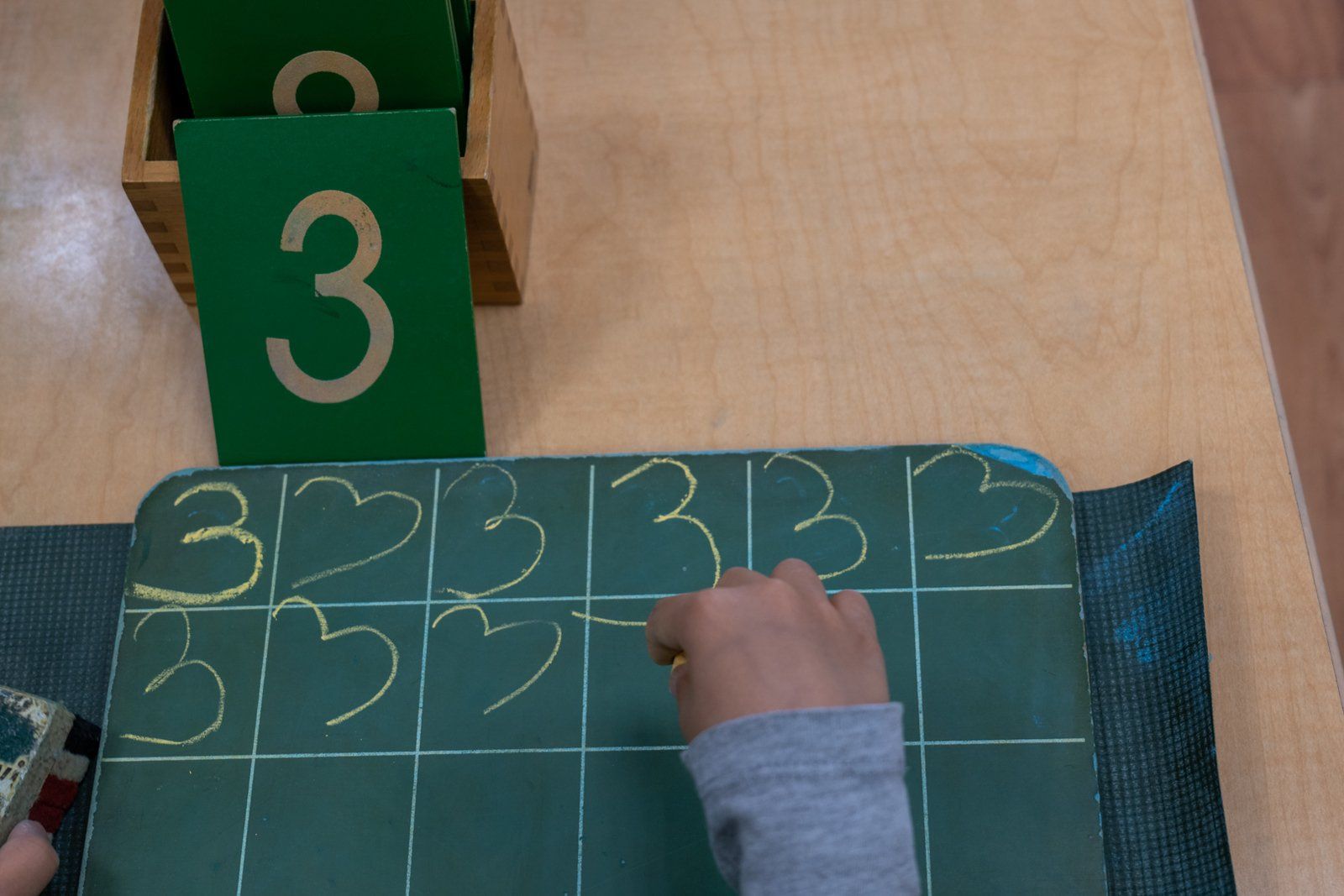

So much of what is taught in school, especially in math is rote learning, abstract, and many students have little idea of how to put their skills to use in everyday life. How does Math make sense? Montessori education works with concrete educational materials first and later introduces abstract concepts once the understanding of the process has been internalized. For instance, in the Sensorial Area we have materials called the Red Rods. The Red Rods are 10 graduated rods, each 10 centimeters longer than the one before. Three-year-old children learn to carry these rods with two hands, one rod at a time to a work rug. As their small arms stretch to carry the last rod that is 100 centimeters long (one meter), they learn the terms short and long, longer, longest as they compare and contrast the 10 rods. This is the very beginning of measurement and base 10 system.

Teachers initiate games to help the child internalize the material. Like having the child close their eyes and the teacher takes one rod away, while closing the gap between rods. The child learns to discriminate the length of rods to know which one is missing.

The corresponding material in the Math Area is the Red and Blue Rods. These rods are identical in size to the Red Rods; however, every 10 centimeters they are painted red or blue, alternating to distinguish their segments. The children are familiar with arranging longest to shortest in a red rod. They count each segment. This material helps them visualize the concept of quantity first and the numeral second – concrete to abstract. By putting a hand around each segment as they count, they are getting the knowledge that counting is moving from left to right and is the numbers are getting bigger.

Later, in a follow up lesson they can put the corresponding numeral card next to the rod. In addition to nomenclature, the students learn about hierarchical inclusion. One is part of two; two is part of three, etc. They can also learn about addition. If I put the one-rod and the two-rod next to each other, they are the same length as the three-rod. They are able to explore similar relationships with all of the rods.

Similarly, the Spindle Boxes provide a way for children to count the correct number of spindles to go into a box with the number indicated. The boxes are labeled 0 to 9. The child picks up each spindle with one hand and transfers it to the other hand, and then into the box, the number grows. One spindle is easy for a small hand to manage. Holding nine spindles in one hand gives a sensory experience of less and more. It is difficult for a small hand to hold them all. Again, this material teaches a very concrete lesson of quantity getting larger. No spindles are put into the box labeled “0”. At a very young age, children are taught that “0” is the empty set.

If the child has counted correctly, there will not be any spindles left over. If there are left overs or not enough, somewhere a mistake has been made. The additional benefit of Montessori materials is the control of error. No person has to tell the child a mistake has been made, the child discovers the mistake and can recount. Part of Montessori’s genius was in the well thought out design of materials and the built-in control of error that allows children to learn from their mistakes.

All of the carefully designed activities that Montessori teachers put on the shelves for children to discover, enjoy and learn have elements of sensory inspiration. The pouring work with jingle bells in the Practical Life area teaches fine motor skills, preparation for pouring dry and wet materials, and makes an enjoyable tingling sound when the bells fall into the dish.

Each material is sequenced on the shelf to move from simple to complex and from concrete to abstract. Materials are sequenced from left to right to help eyes move in that direction – for preparation of reading. Teachers get to know exactly where each child is in the sequence of materials to make sure that there are activities that are comfortable because the child worked with or mastered the activity before. There are also activities that provide challenge to stretch the learning and imagination going forward.

“Our care of the child should be governed, not by the desire to make him learn things, but by the endeavor always to keep burning within him that light which is called intelligence.” ~ Maria Montessori